Assumed audience: People interested in the nitty-gritty details of music notation software transfer formats.

Last weekend I noted that I had hit a number of frustrations in trying to jump back and forth between StaffPad and Dorico, because the MusicXML handoff between the two was frustrating particularly around percussion — and, spoilers, my orchestral writing makes pretty thorough use of percussion!1 While I’m still somewhat up in the air where I’ll ultimately land on one or the other as a primary tool — recent news from Dorico having made that a yet more interesting consideration!2 — in the meantime I figured it would be interesting to dig into how and why the two differ.

For this post, I’m going to dig into the major ways the applications differ in how they represent a single percussion instrument: wood blocks. I picked wood blocks because they’re a bit move involved than something like a bass drum or snare drum:

-

They are categorized as unpitched percussion, because they do not have definite pitches, but they do have distinct pitches across the blocks.

-

They are always represented as some kind of multiline staff. However, different tools present that staff differently!

-

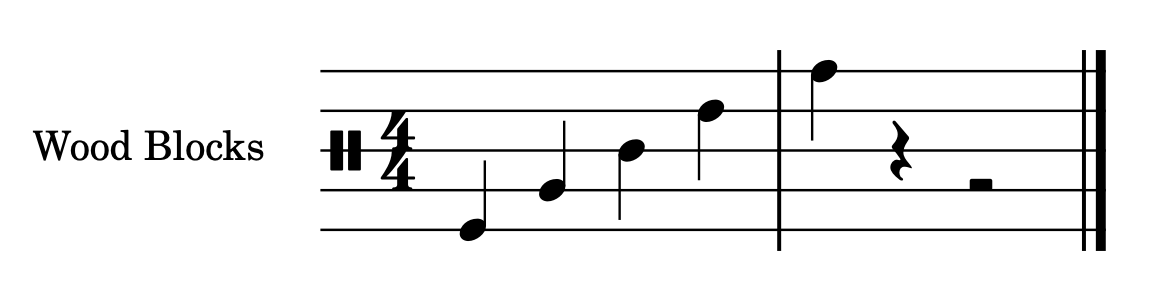

StaffPad uses by a traditional 5-line staff:

-

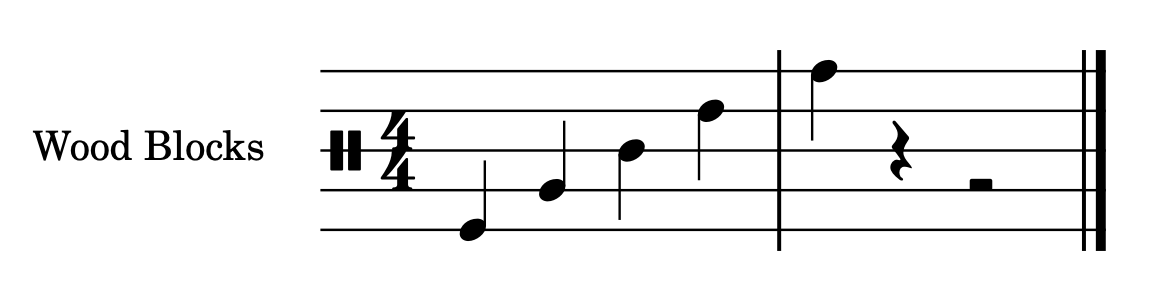

Dorico uses a line-per-block percussion-style staff:

-

-

They are not a collection of totally different percussion instruments all grouped together as in a drum kit staff, but the blocks do also have distinct elements to strike in a way that differs from e.g. a piano or a glockenspiel.

This set of differences means that looking at wood blocks will show us most of what we need to know about the underlying differences in the programs’ representations of percussion. We can safely generalize from what we’ll see below!

Presentation

First, notice again the two different visual representations of the instrument.

StaffPad:

Dorico:

This gives us our first hint of how the two programs model the instruments differently: StaffPad is treating this as an unpitched instrument in some ways (notice the two-thick-bars start of the staff), but using a pitched-instrument-style staff to represent it. Dorico is doing something totally different, with a single line per block — as if it is representing each wood block as a distinct instrument, but grouped together into a single visual representation. As it turns out, that visual difference (apparent here as it is not necessarily in other, simpler percussion instruments we might have looked at) is exactly what is going on under the hood.

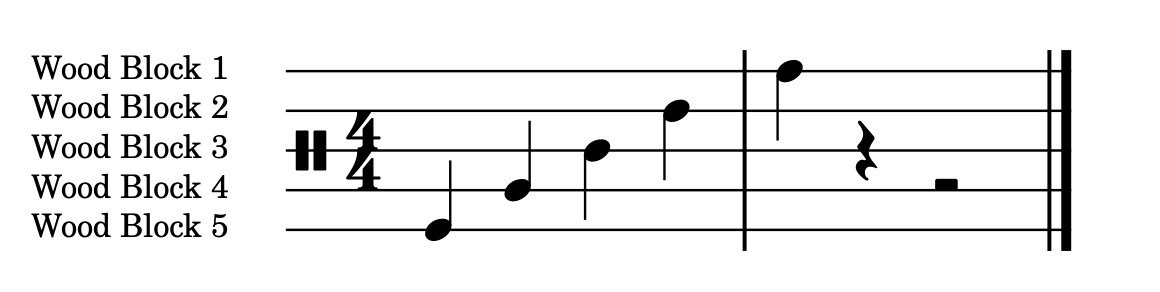

What’s more, I have actually cheated a bit here to make these appear more similar than they normally would. By default, Dorico actually presents these with the individual blocks named:

I went out of my way to create a Group to get the notation as close as possible to StaffPad’s to highlight the difference in presentation of the musical staves, but with the default instrument naming in view it becomes that much more clear: Dorico thinks of each block as a distinct item on unpitched lines, whereas StaffPad thinks of them as a single instrument with unpitched blocks mapped to pitched stave lines, and they present them accordingly.

So how does that translate into the MusicXML each program generates?

MusicXML Representation

There are a couple points of interest here. One is how the instruments themselves are defined. Both programs follow the MusicXML spec here, but they represent the instrument quite differently — albeit in a rather unsurprising way, given what we saw above!

Here’s how StaffPad defines the wood blocks instrument:

<part-list>

<score-part id="P1">

<part-name>Wood Blocks</part-name>

<score-instrument id="P1-I1">

<instrument-name>Wood Blocks</instrument-name>

<instrument-abbreviation>W.Blocks</instrument-abbreviation>

<instrument-sound>wood.wood-block</instrument-sound>

</score-instrument>

</score-part>

</part-list>

And here’s how Dorico defines the wood blocks instrument:3

<part-list>

<score-part id="P1">

<part-name>Wood Blocks</part-name>

<score-instrument id="P1-X1">

<instrument-name>Wood Block 1</instrument-name>

</score-instrument>

<score-instrument id="P1-X2">

<instrument-name>Wood Block 2</instrument-name>

</score-instrument>

<score-instrument id="P1-X3">

<instrument-name>Wood Block 3</instrument-name>

</score-instrument>

<score-instrument id="P1-X4">

<instrument-name>Wood Block 4</instrument-name>

</score-instrument>

<score-instrument id="P1-X5">

<instrument-name>Wood Block 5</instrument-name>

</score-instrument>

</score-part>

</part-list>

The key things to notice here:

-

StaffPad and Dorico both treat this instrument as a single

score-part, and in fact it happens to have a matching part ID (because they are both the first/only instrument in the score). -

In StaffPad, the wood blocks are represented as a single

score-instrumentwithin that top-levelscore-part. In Dorico, each wood block is a separatescore-instrumentandinstrument-namewithin thescore-part.

The result is what I found last week: The different lines from percussion instruments from StaffPad ended up mapped into multiple different instruments in Dorico.

This continues as we dig into the <part> section of the MusicXML file. A <part> represents each musical part in the score, and holds all the measures which belong to that part. If we look at how the two programs represent the parts, we can see more of why it’s difficult to translate from one to the other.

StaffPad:

<part id="P1">

<measure number="1">

<attributes>

<divisions>192</divisions>

<key>

<fifths>0</fifths>

<mode>major</mode>

</key>

<time>

<beats>4</beats>

<beat-type>4</beat-type>

</time>

<staves>1</staves>

<clef>

<sign>percussion</sign>

</clef>

<staff-details>

<staff-lines>5</staff-lines>

</staff-details>

<transpose>

<diatonic>0</diatonic>

<chromatic>0</chromatic>

<octave-change>0</octave-change>

</transpose>

</attributes>

<!-- ... <note>s... -->

</measure>

</part>

Dorico:

<part id="P1">

<measure number="1">

<attributes>

<divisions>4</divisions>

<key number="1">

<fifths>0</fifths>

<mode>major</mode>

</key>

<time>

<beats>4</beats>

<beat-type>4</beat-type>

</time>

<staves>1</staves>

<clef number="1">

<sign>percussion</sign>

</clef>

</attributes>

<!-- ... <note>s... -->

</measure>

</part>

The first thing to notice4 is in the staff-details definition. Here’s a table showing a quick comparison:

| Element | StaffPad | Dorico |

|---|---|---|

clef |

percussion |

percussion |

staves |

1 |

1 |

staff-lines |

5 |

N/A |

transpose |

default values | N/A |

Both use percussion for the clef (though Dorico explicitly also specifies a clef number attribute here), and set staves to 1 for this part, as we would expect: most instruments other than a piano, harp, or similar will be single-stave instruments. Beyond this, the two diverge substantially. StaffPad specifies staff-lines (within the staff-details container), but while it could choose to use the line-detail element to represent this exactly the way Dorico does… it doesn’t do that. Instead, it just specifies that there are five staff lines and moves on. Meanwhile, Dorico skips this entirely, because it has encoded the representation of the blocks already: in the part-list at the top. Likewise, Dorico doesn’t specify transposition at all, because it’s not relevant information for this instrument.5

This pattern continues when we look at individual notes. Let’s see how each program represents the first note, the lowest wood block. (The rest of the notes are basically identical, just with differences around which block is being struck.)

First, StaffPad:

<note>

<pitch>

<step>G</step>

<octave>4</octave>

</pitch>

<duration>192</duration>

<voice>1</voice>

<type>quarter</type>

</note>

Now Dorico:

<note>

<unpitched>

<display-step>E</display-step>

<display-octave>4</display-octave>

</unpitched>

<duration>4</duration>

<instrument id="P1-X5"/>

<voice>1</voice>

<type>quarter</type>

<stem>up</stem>

<staff>1</staff>

</note>

This time Dorico has far more information, but this is because it is encoding the wood blocks as genuinely unpitched and representing them as separate instruments, as we saw in the part-list. StaffPad is representing that first note as a pitched note: a “G4”. Dorico is representing it as an unpitched note which is displayed as “E4”. In this case, while StaffPad’s representation is not unknown in published music, Dorico’s is definitely the more correct representation. You can also see that as a result of the choice to represent the blocks as individual instruments, Dorico needs to specify the instrument with an id attribute, and to specify the staff number on which the note is set. Those latter bits come “for free” for StaffPad because of its choice to use a pitched representation of the note, but at the cost of a representation which has technically-incorrect semantics.

It’s worth pausing here to note that a program could choose an alternative to Dorico’s representation which would also be correct. For example, you could use the line-detail element for the different lines within the stave, and take the same approach with unpitched notes and a display-step and display-octave as Dorico does. (The point is not that Dorico does it correctly — though I think it does — so much as that StaffPad does it slightly incorrectly.) But even so: the format is flexible enough that interop would be hard regardless. It is not obvious to me that Dorico’s import would work any better at all if StaffPad switched to the encoding I described here. This is just a hard problem!

So what?

As we come here to the end, you might be wondering what the point of all of that was. Well, for one thing I hope it’s helpful for other people besides me to see exactly what’s going on in this musical interchange format. Understanding the complexities of these kinds of things can make it easier for people to sympathize with software developers: whose work is very hard!6

For another, I started digging into this to see how hard it would be to write a small tool to transform StaffPad’s output into something Dorico will understand. I think the answer is: not too hard! I would need to go through each kind of percussion instrument and make sure it transforms it correctly, but that’s the kind of thing I know how to do from other sorts of XML-mashing in the past.7

While I don’t know that I’ll do that, I now have a pretty good sense of what it would take. It would be some non-trivial amount of work, to be sure; but depending on what my ongoing workflow looks like, it might end up being worth it to me. If it does and I build that tool, I will of course share it here as well as in various forums for the software programs in question. (No promises, though, for real!)

If you’re curious and want to dig in further yourself, I‘ve uploaded both of the MusicXML files used in this discussion; feel free to take a look:

Notes

A thing even most of my long-time readers likely don’t know: once upon a time back in high school, I played percussion in the wind ensemble. I enjoyed it and learned a lot. ↩︎

POWAHHHRR, UNLIMITED POWAAHHHHRRRR — err, sorry, I meant unlimited parts on Dorico for iPad. ↩︎

Folks knowledgeable about Dorico may be interested to know that this is true regardless of whether the wood blocks are in a group in a percussion kit. ↩︎

There are also differences in how

<divisions>,<key>, and<time>are handled. This is interesting, and I strongly suspect it points to other deep-seated differences in how the two programs conceptualize/model music, but doesn’t matter for our purposes today. ↩︎This is almost certainly not a case of consciously choosing on some per-instrument basis what to do. Rather: the programs specify how to export the XML for a given bucket of data, and then it goes automatically. So, most likely, StaffPad has a representation of transposition for every instrument, even if it’s defaulted, as here, to nothing-interesting, move along; while Dorico likely doesn’t have it for the instruments like this at all. The XML export just reflects that internal representation. ↩︎

I have a vested interest in that, even if I don’t (currently?) work in music notation software. ↩︎

Turns out that working with the OSIS representation of the KJV Bible back when I built HolyBible.com the better part of a decade taught me a lot of useful things. ↩︎